Language Modeling, Part 5: Reverse Engineering LSTM Cells

In Part 5 of this series on language modeling, we linger a bit on the LSTM to peek under the hood in order to better understand the network’s internals. If you’re just joining, you can read Part 4 here. Our latest 1-layer LSTM we trained from Part 4 on the TinyStories dataset generates stories such as:

Once upon a time there were two fearful of many toys. They do not notice their fight. They liked to give the chimding into his room. There, they had a doll, I cut the brush to go away. Let’s decide it rown in your bones and your bike, Ben. You are brave and selfish.” They ask Mom and Dad.

“Go?” Lily said, pointing at the balloon. She hugged the doll bitter. She opened her around with her window. One day, she noticed something giragain and the airport. The little bird flew away, curious, and told her family for being so much fun.

Timmy felt happy with his game and went to her mom and stayed because no one wanted to see the flower. Lily realized that being happy she and Lily, was very surprise

These stories are so good I’m going to have to start charging a subscription! Kidding, and if you decide to tell this one to your kids I’m not responsible for their resulting nightmares or subsequently poor English proficiency.

Ok so the story has a few invalid words and is incoherent nonsense overall, but the syntactic structure the model has learned to generate is pretty good. In particular you can see it has mostly figured out quotations as well as punctuation, spacing, and some subject-verb agreement.

What I want to do in this post is probe the internals of the model to map out where different capabilities live. For example, can we find the hidden unit(s) responsible for recognizing quotation marks? What about other punctuation, or particular words? Can we control the expression of these capabilities by modifying the hidden units in a particular way? Most of these questions are inspired by Karpathy’s excellent paper Visualizing and Understanding Recurrent Networks. I recommend that paper for good background material. Let’s explore these questions in the next section.

Visualizing LSTM Cells

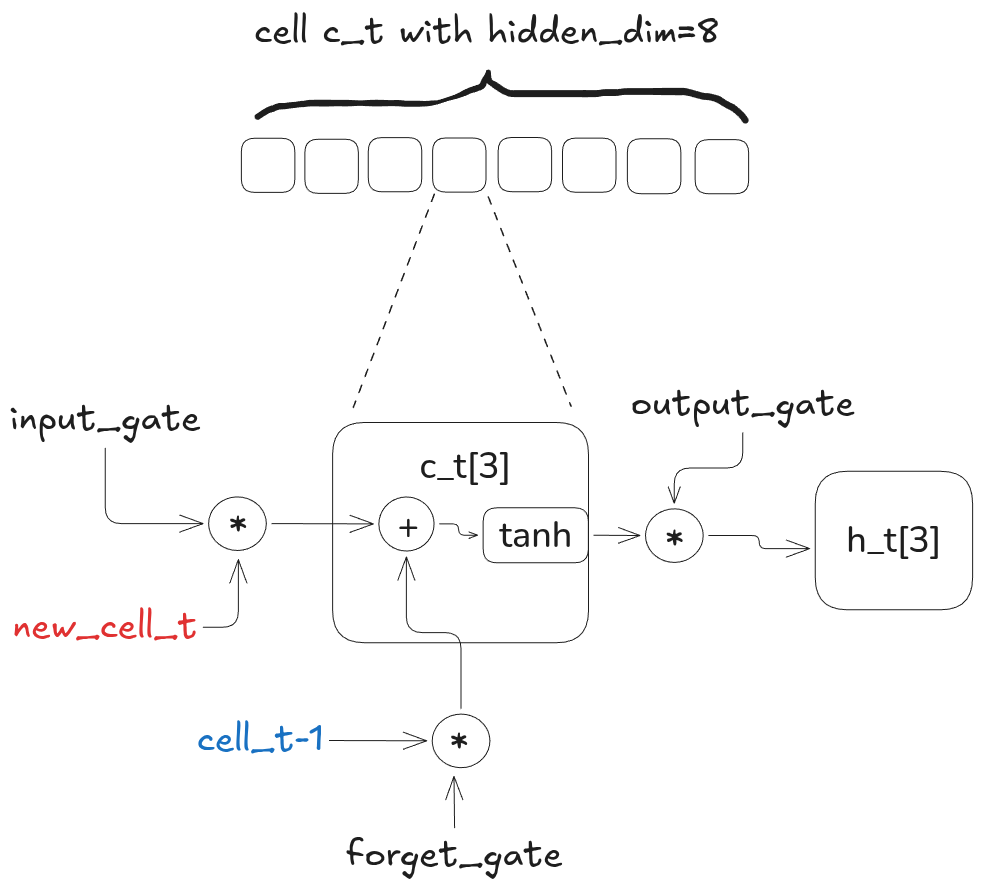

Recall the structure of the LSTM:

The example cell above has only 8 hidden units (hidden_dim=8) for drawing purposes. The LSTM that we trained in Part 4 uses a cell with 256 hidden units (note I’m going to refer to “hidden unit of the cell” as just “cell”).

If we want to attribute different cells to various aspects of the input, we can generate a trace of the activation values of each cell for a given string. There is one activation value per token of the input string. This string can contain tokens of interest, such as vowels, quotes, and other punctuation. Then we can scan the activation maps of each cell to look for patterns.

Here is the code for generating a trace:

# Collect all activation values of cell @cell_idx. In the

# LSTM there are 256 total cells (note the "cell" usually refers to

# the entire memory cell of the LSTM - I'm abusing the terminology

# here slightly by referring to a particular hidden unit

# (given by @cell_idx) within the cell as "cell").

def trace_cell(lstm, string, cell_idx):

assert cell_idx < lstm[1].hidden_dim # 256

hidden = cell = None

activation_trace = []

for char in string:

c = torch.tensor(stoi[char], device=device)

# Embed the token

x = lstm[0](c)

x = x.unsqueeze(dim=0).unsqueeze(dim=0)

# Generate prediction

x, hidden, cell = lstm[1](x, h=hidden, c=cell)

# assumes cell is (1, hidden_dim)

activation_trace.append(cell[0][cell_idx].item())

return activation_traceYou can see the full code for this here. When you run this for each cell with the input string:

Once upon a time, there was a girl named Lucy. Lucy asked Bob, “Why did the chicken cross the road?”

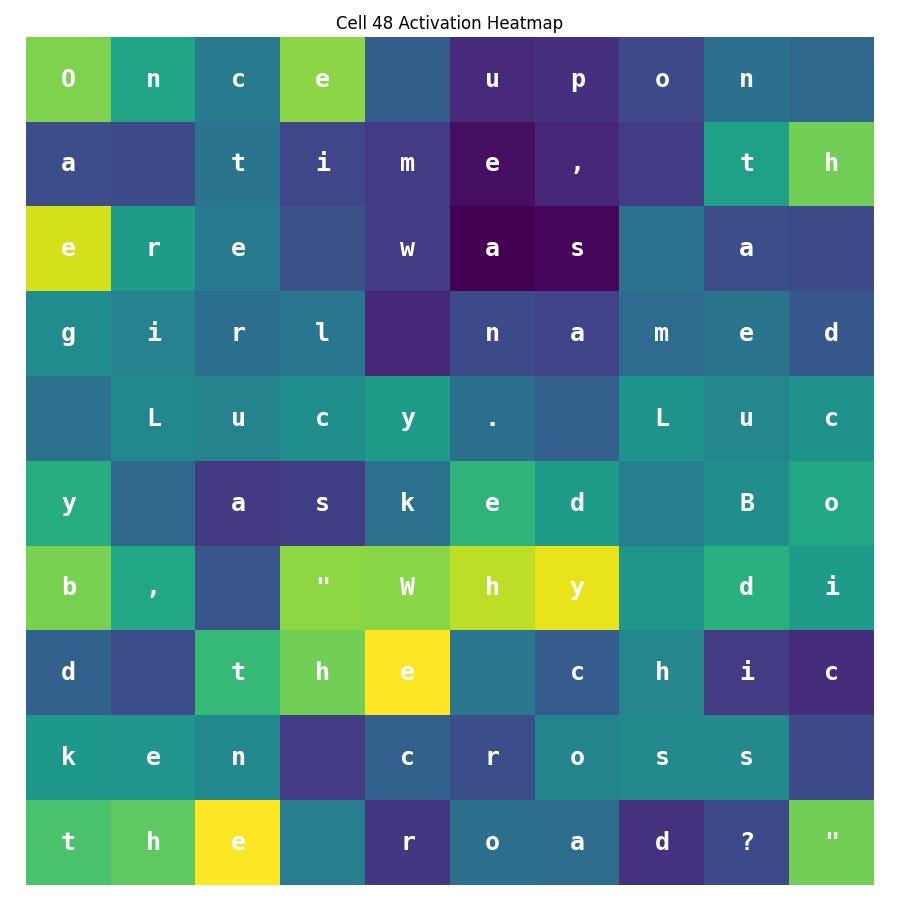

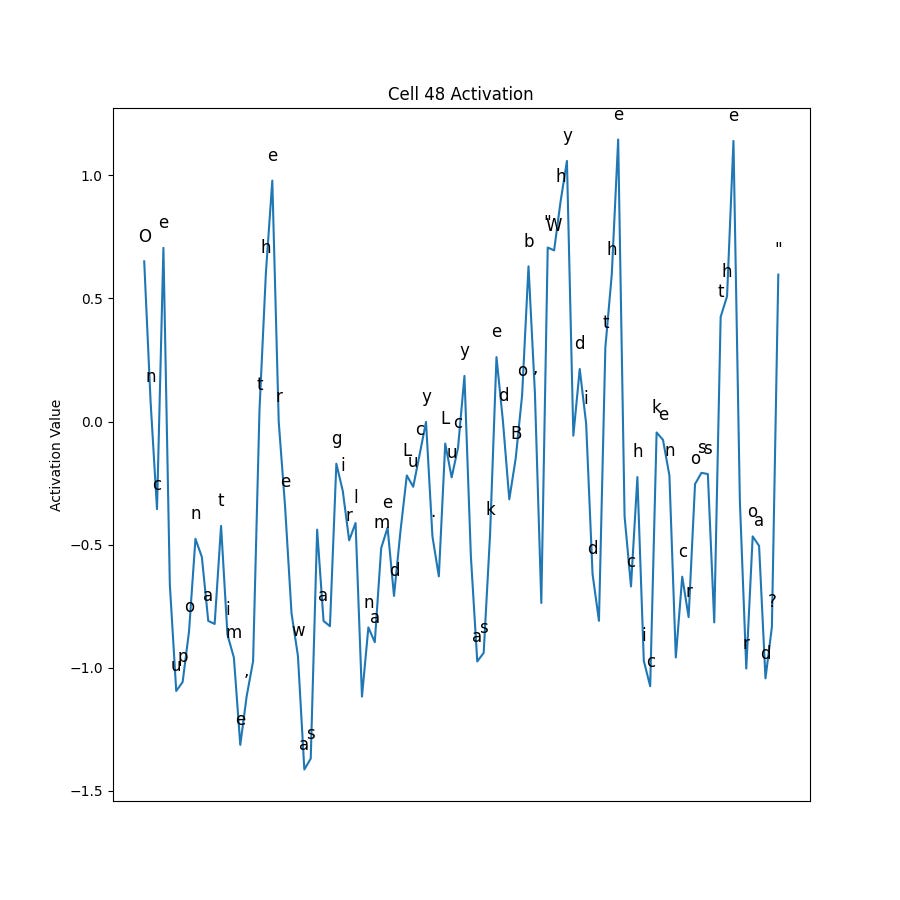

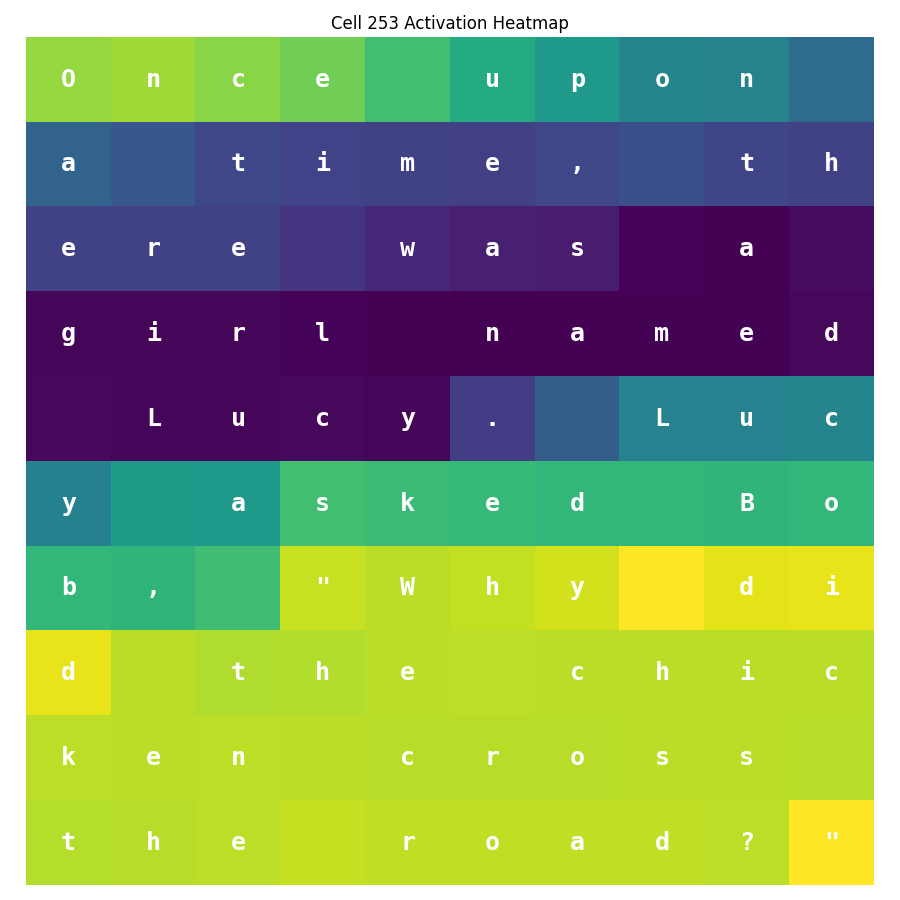

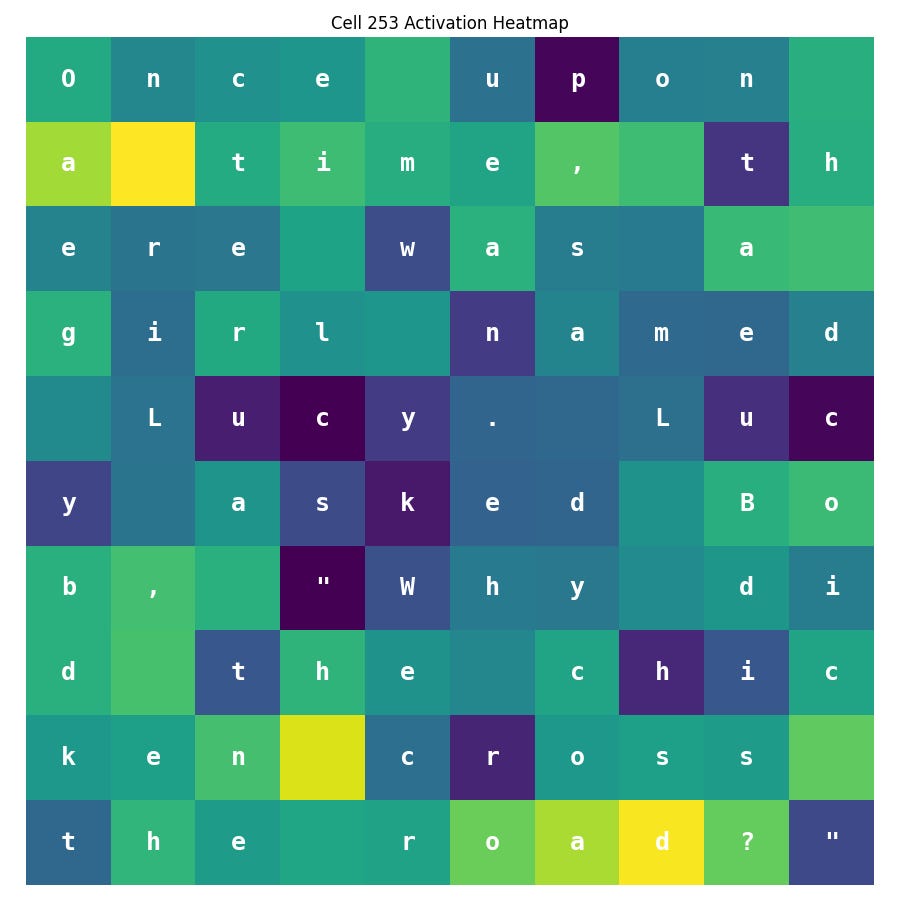

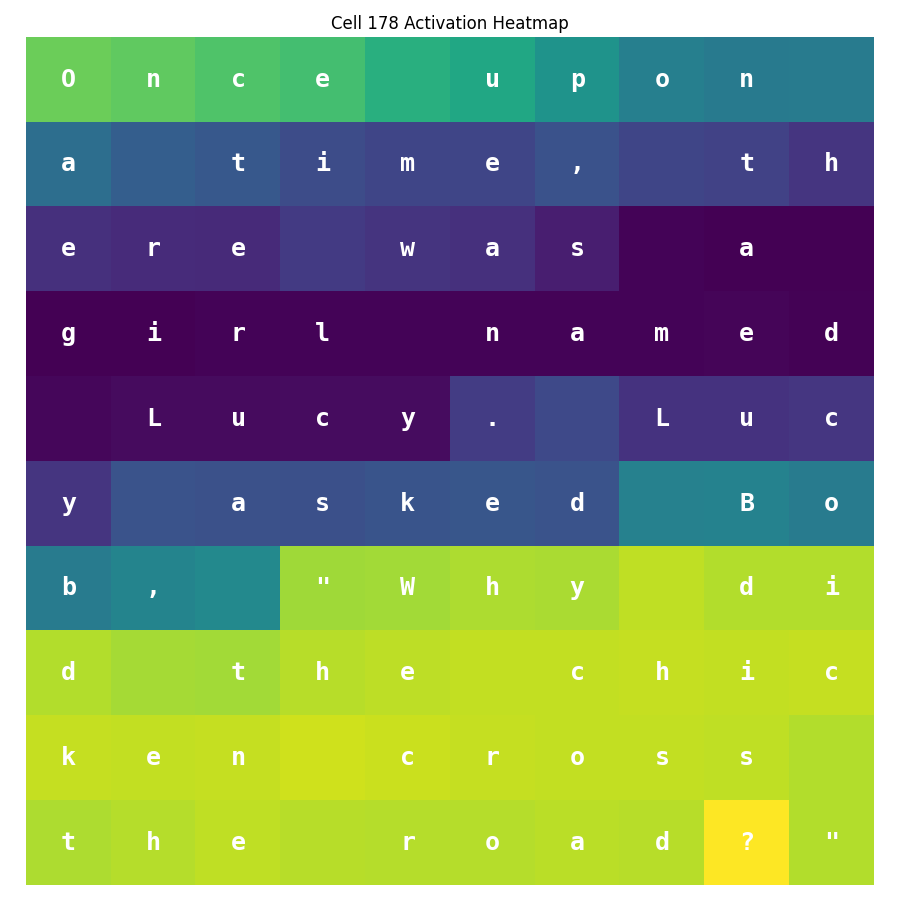

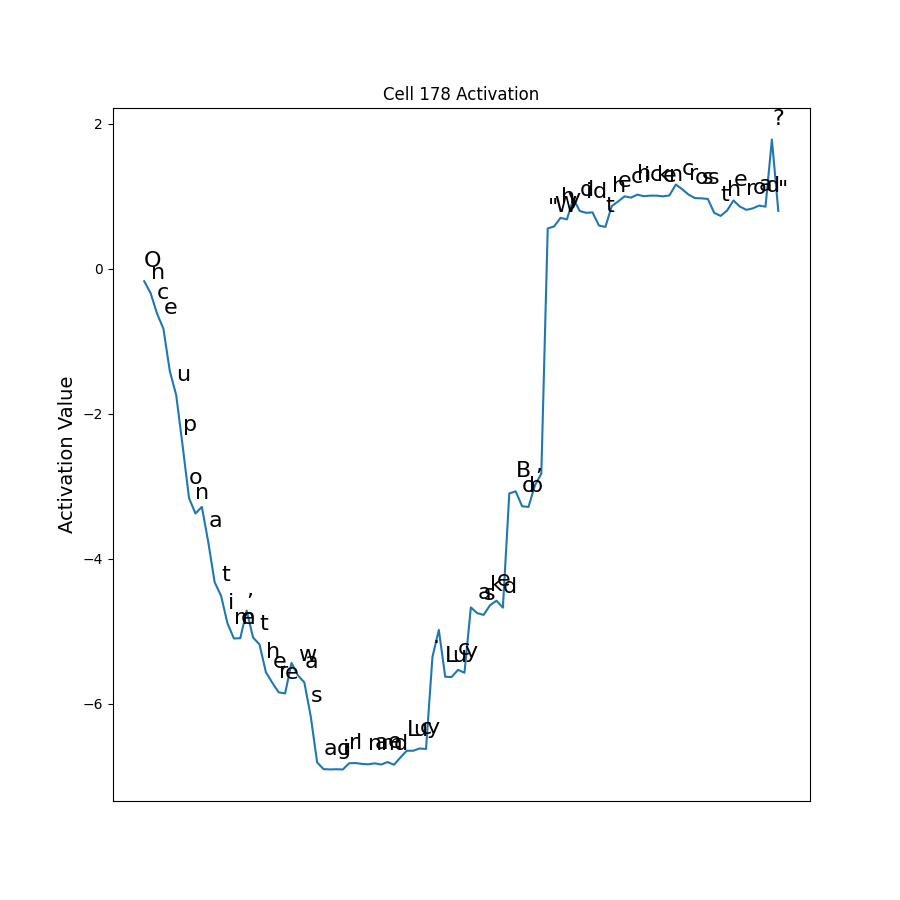

we see some interesting patterns emerge. Note in the activation heatmaps below, purple means the cell is not activated, greenish is neutral, and yellow is highly activated. The corresponding line plot of the activation values versus token is below each heatmap.

Here is Cell 48:

Cell 48 is fairly noisy, but appears to be excited by sequences ending in ‘e’ and ‘y’ like ‘Once’, ‘the’, and ‘Why’.

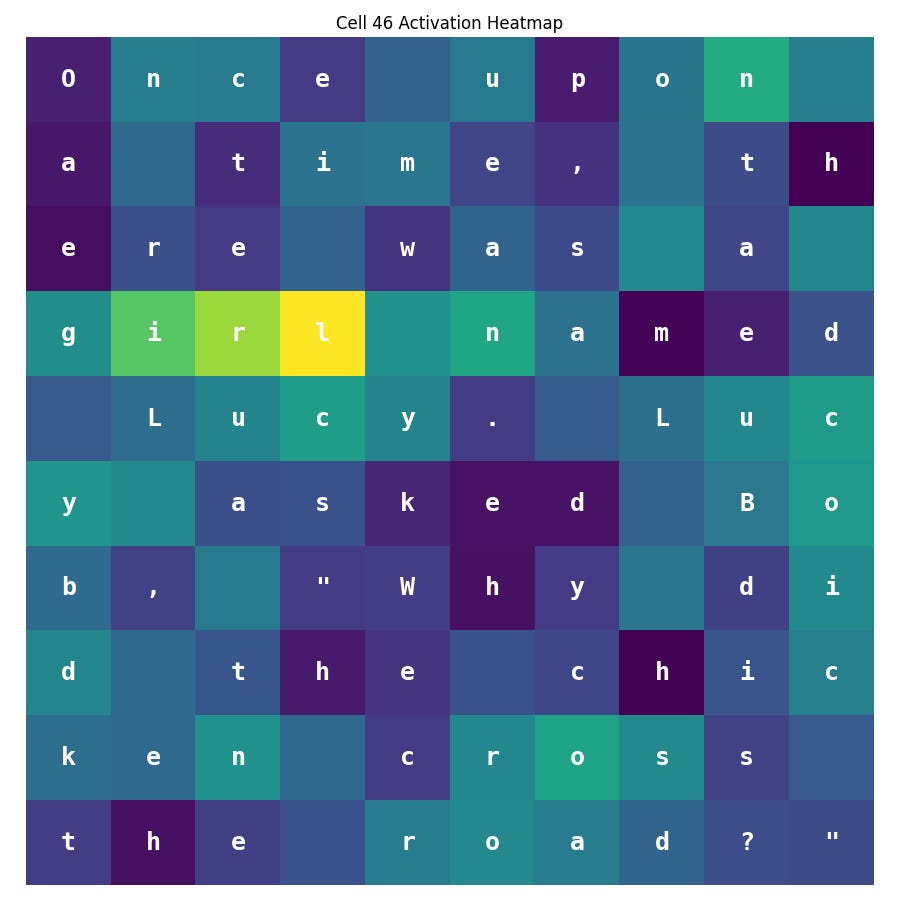

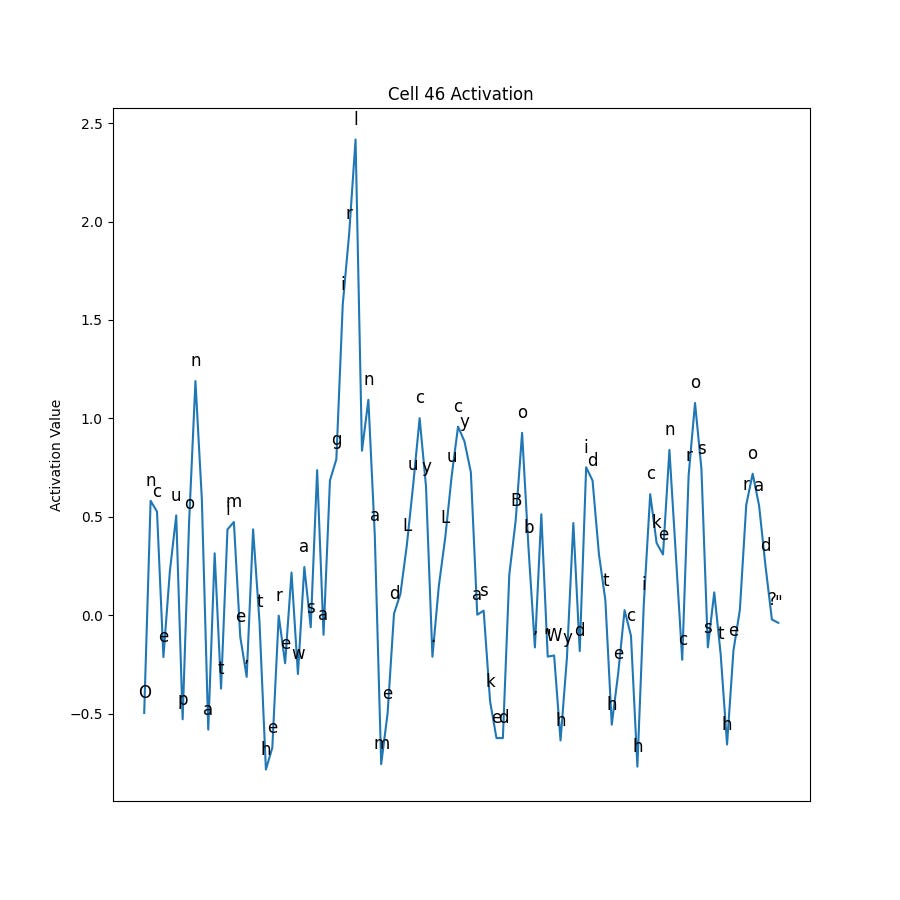

Let’s look at Cell 46:

It seems to only get excited about ‘girl’. Of course to verify this, we would need to test with other input strings containing ‘girl’ in different positions, and also with ones not including ‘girl’ at all.

Now check out Cell 253:

It looks like a cell that is signaling for quoted strings, since the activations of the quotes themselves are as active as the quoted content. The activation is negative until is sees the first quote, then stays positive every token in the quoted string, including the last quote. The large dip prior to the quote is quite puzzling!

At this point there are more questions than answers. For example, if we retrain the model will we see the same cell patterns at the same cell index? How do the input, forget, and output gates behave in relation to the activations we are seeing? What would happen to the model’s capabilities if we nerf a cell? Let’s double click on this last cell to explore some of these questions.

Digging Deeper Into the Quote Signaler

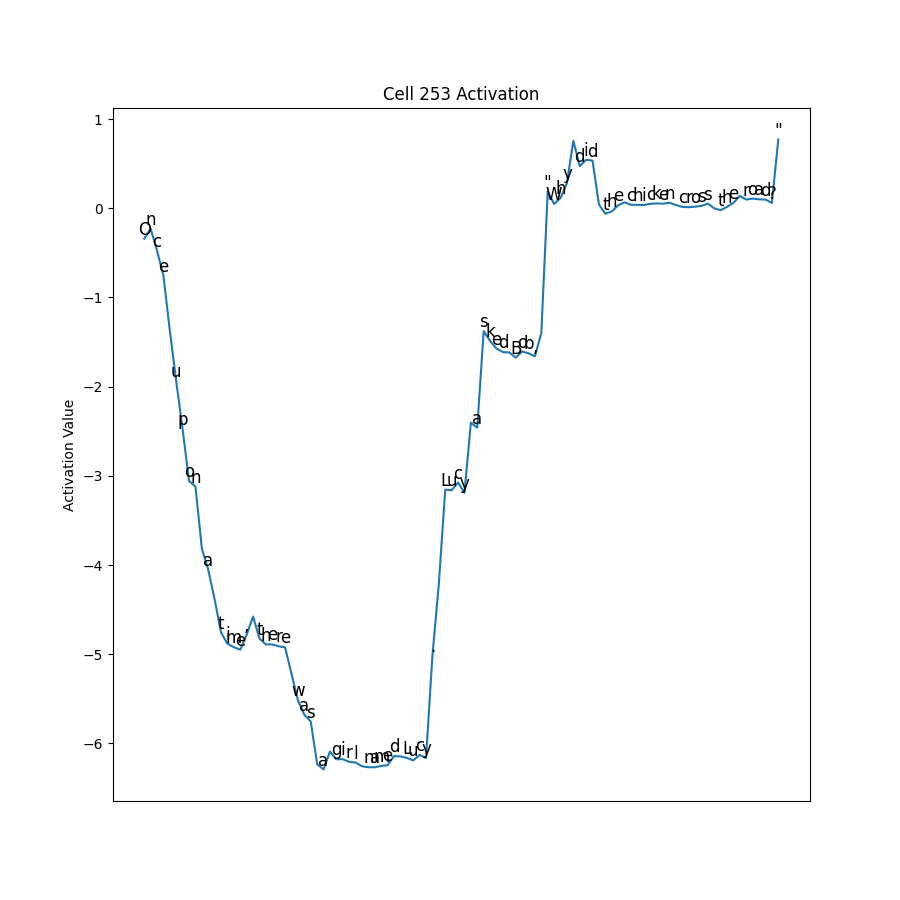

I retrained the single-layer model to see if the cell patterns were stable. Here is the plot of Cell 253:

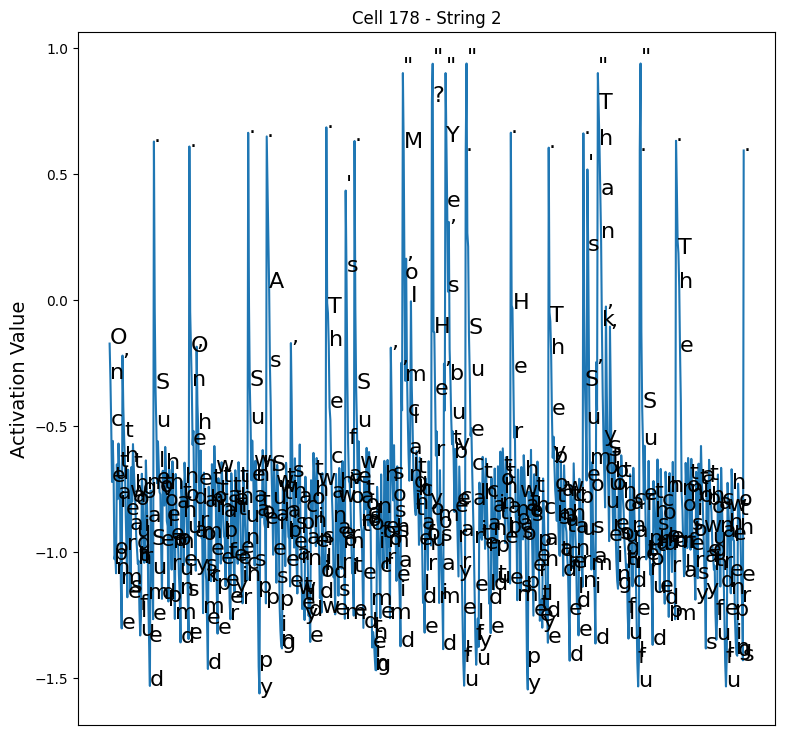

It’s different! What happened? I had to look through all cells in the new model to see if it had moved. Sure enough I found it, but this time at cell 178:

Why did it move? Turns out that I had been accidentally initializing the weights of the model without a constant-seeded random number generator. This means the weights had different initial values than the first run. That is the only difference I can think of. It is not obvious exactly why this would cause it to move to cell 179 instead of staying at 253, but it is very interesting that the model learned it regardless. Roughly the same pattern holds - activation is negative outside of the quote, and positive inside the quote.

Analyzing Gates

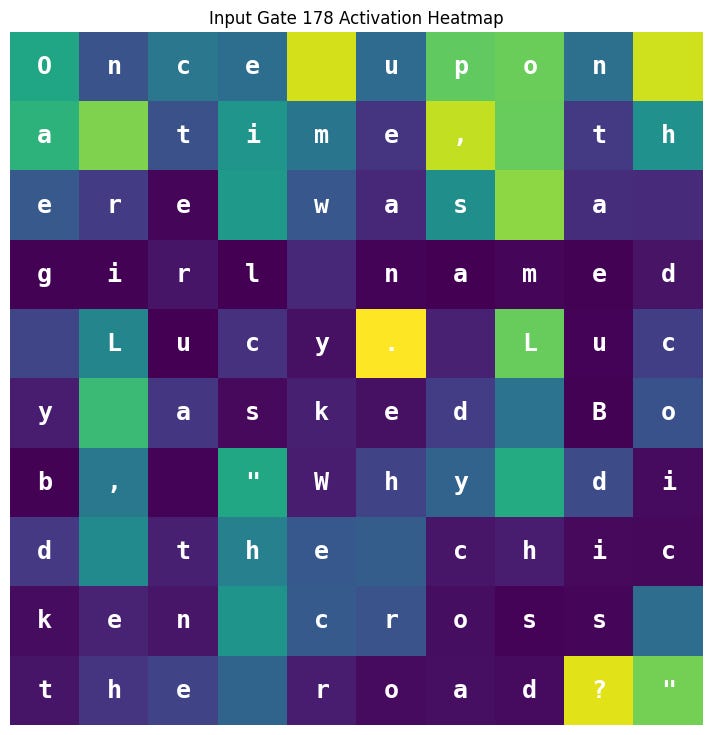

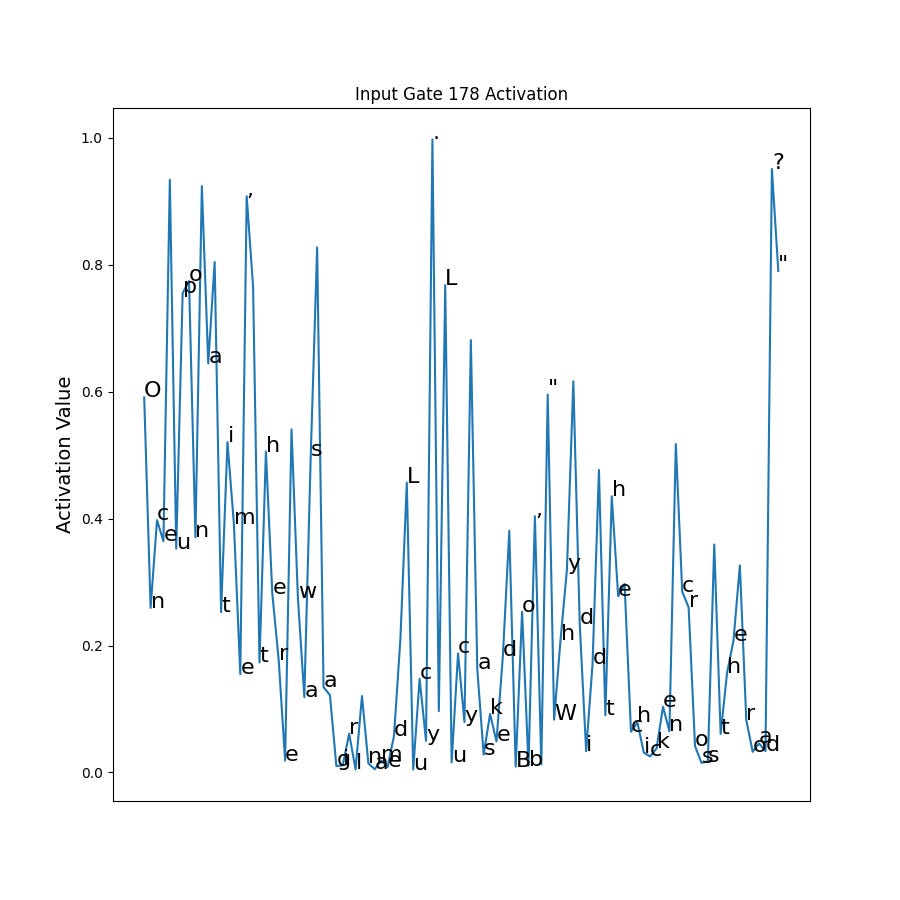

Now lets turn to the gates’ behavior. We can create the same heatmap and line activation plots to see how the gates react as the input proceeds. Recall the input gate controls how much of the current token’s representation to let into the cell. So an activated input gate is excited about the current token and wants to ensure it is represented in the cell. An input gate that is deactivated doesn’t want to let that input in the cell.

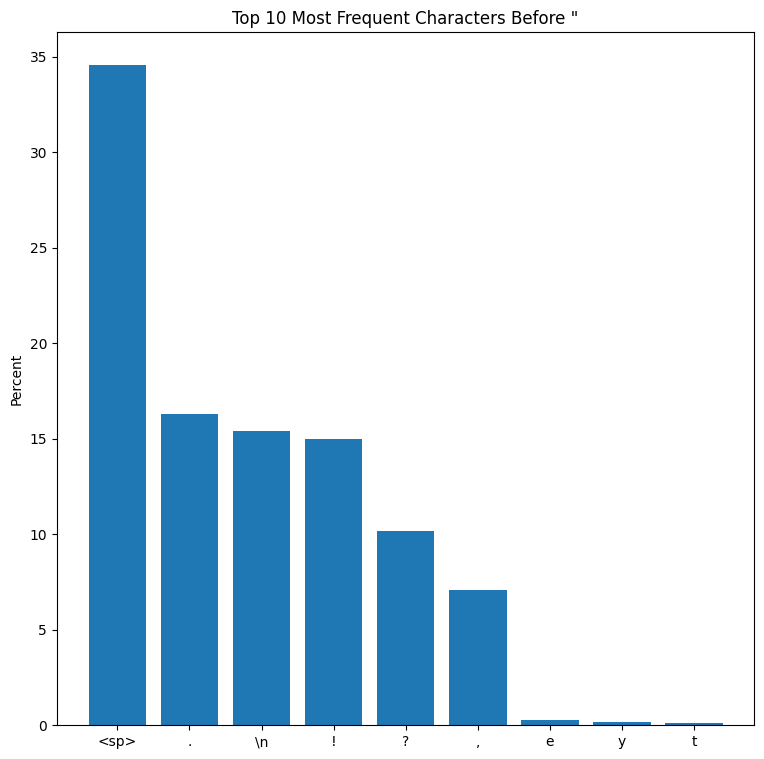

The input gate is fairly noisy, especially at the beginning. In general though it seems to activate for spaces and punctuation. This would make sense for a gate trying to signal for quotes, since for this particular dataset, a large percentage of quotations are preceded by spaces and punctuation. You can see this by calculating the frequency statistics of all characters that precede a quote. For TinyStories, this distribution follows a power law:

What is really fascinating is that initially the gate is interested in spaces, but that interest fades as the sequence gets longer. However the interest in punctuation remains elevated throughout.

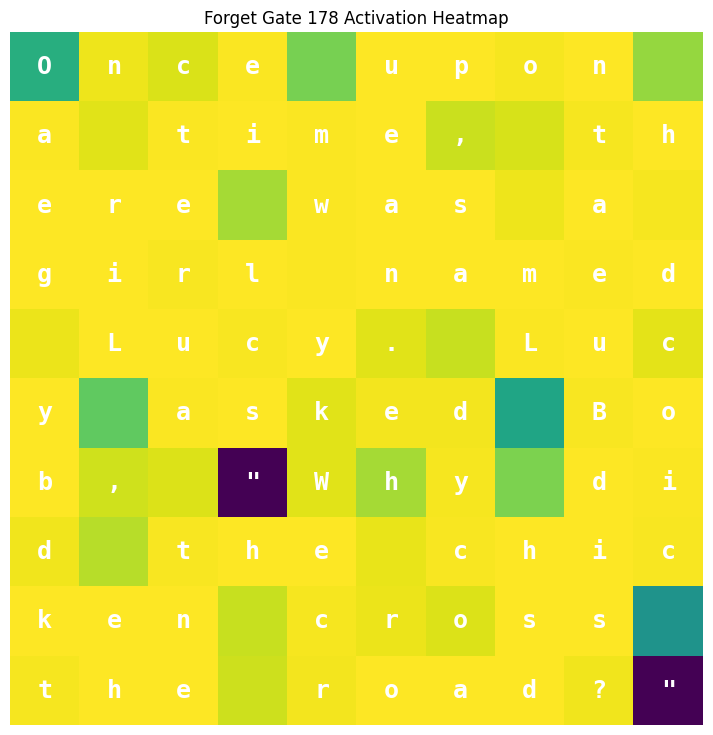

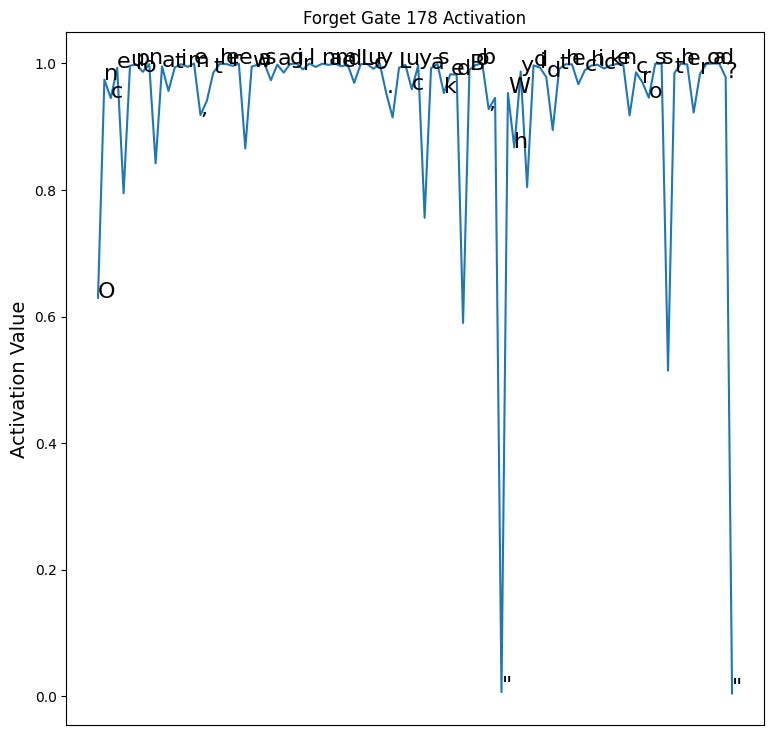

Let move on to the forget gate. Remember the forget gate is “active low”. When the forget gate is high, it wants to retain the previous cell’s representation in the current cell. If it is low, it wants to remove the previous cell’s representation from the cell. Here is the heatmap:

You can see it partially retains the beginning character and in general holds high, retaining the cell’s state until it reaches the first quote, where it then completely clears the prior cell’s representation from the current cell value. This means the cell’s value for the quote token is whatever is passed through the input gate, which happens to be a fairly strong representation of the quote itself, based on the input gate activation above. It then immediately activates near 1 on the next token and holds high until the next quote. The forget gate seems to be implementing a primitive state machine of {inside quote, outside quote}, where transitions occur whenever a quote is encountered.

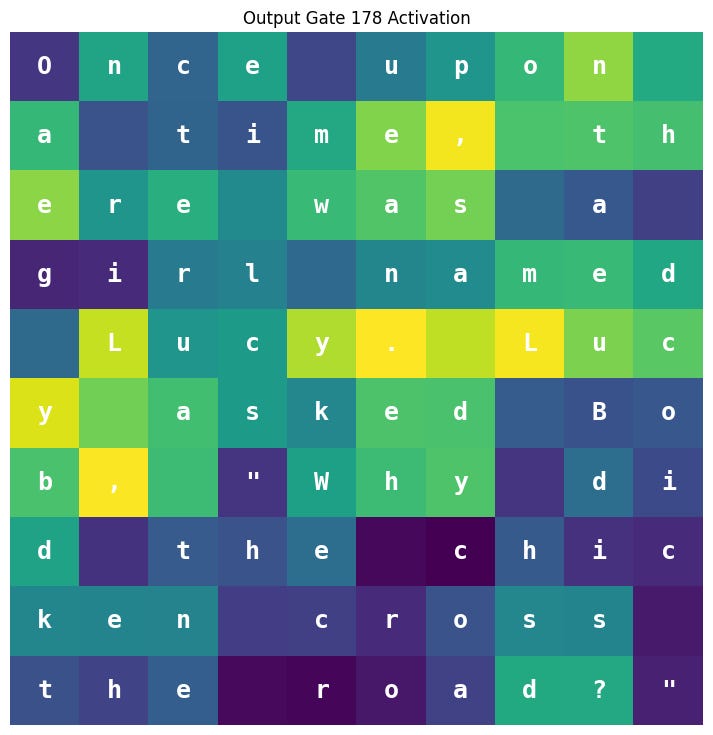

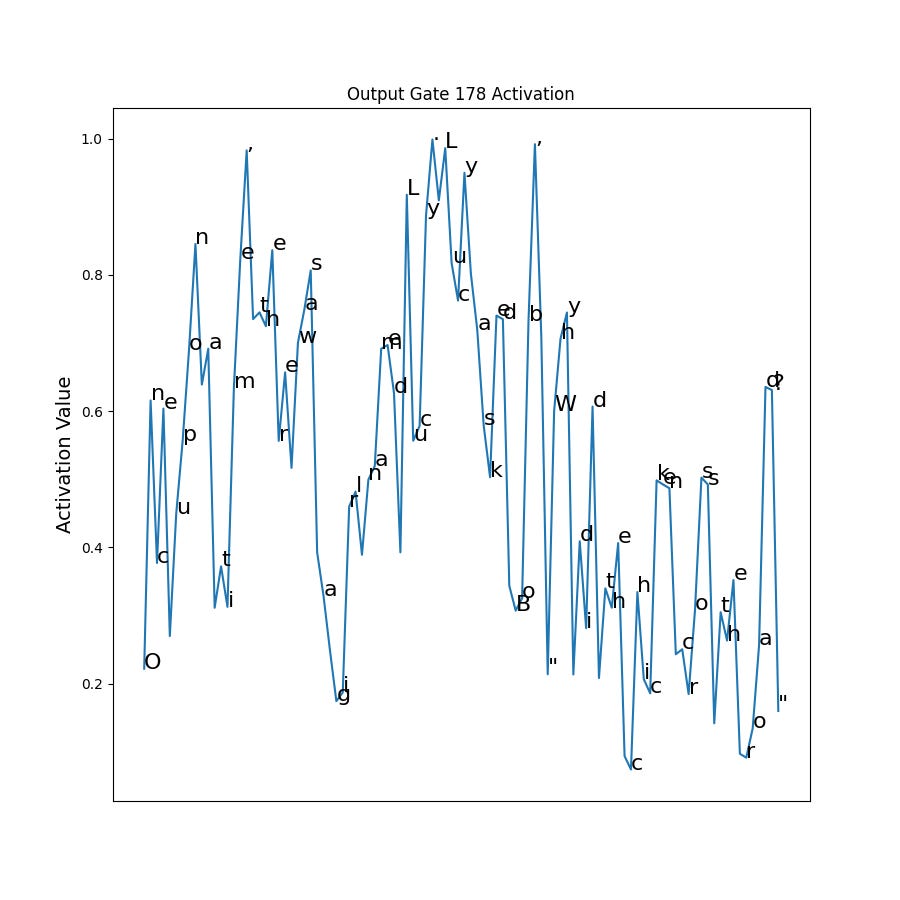

Finally let’s look at the output gate. The output gate controls how “strongly” the cell’s representation is written into the hidden state. A value of zero resets the hidden state, whereas a value of one copies the cell verbatim into the hidden state.

This one is a bit harder to interpret than the forget gate. One thing to notice is that none of the activations are zero. So every token has at least some of the cell being written to the hidden state. We also see that on average, the output gate is more activated before the first quote. However there are “near clearing” events before and after the quote, so it isn’t clear how that is being used. It is notable that the punctuation activations are high. Combined this with the high punctuation activations for the input gate and forget gate, it suggests the output gate has learned to let the punctuation flow into the hidden state.

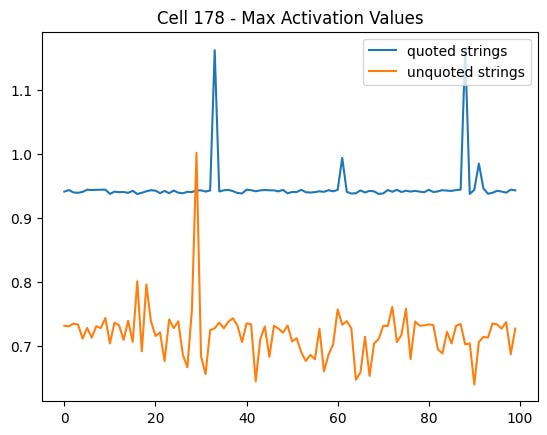

The running hypothesis is that this cell encodes a state machine, where the cell activation is negative when outside of quotes, and positive when inside quotes. We can re-trace the cell on different inputs to see if this holds up. I created two sets of strings from the validation set - 100 quoted and 100 unquoted. I then traced cell 178 on each string.

Here is a plot of the maximum activation values across all strings:

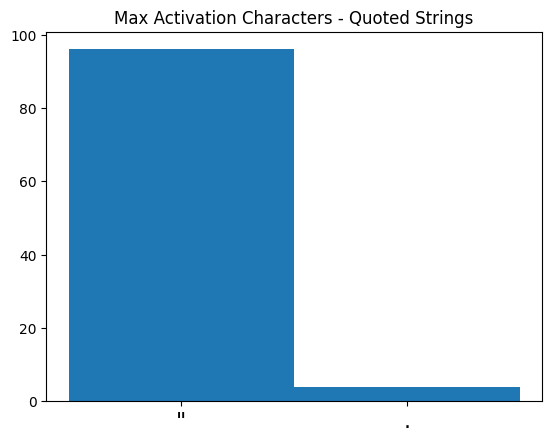

So we’ve falsified the hypothesis, since the unquoted strings have positive values despite not having any quotes. However the quoted strings consistently (except for one string) have a max that is greater than the unquoted strings. The majority of the time (96%), the character that gives the max activation is the quote:

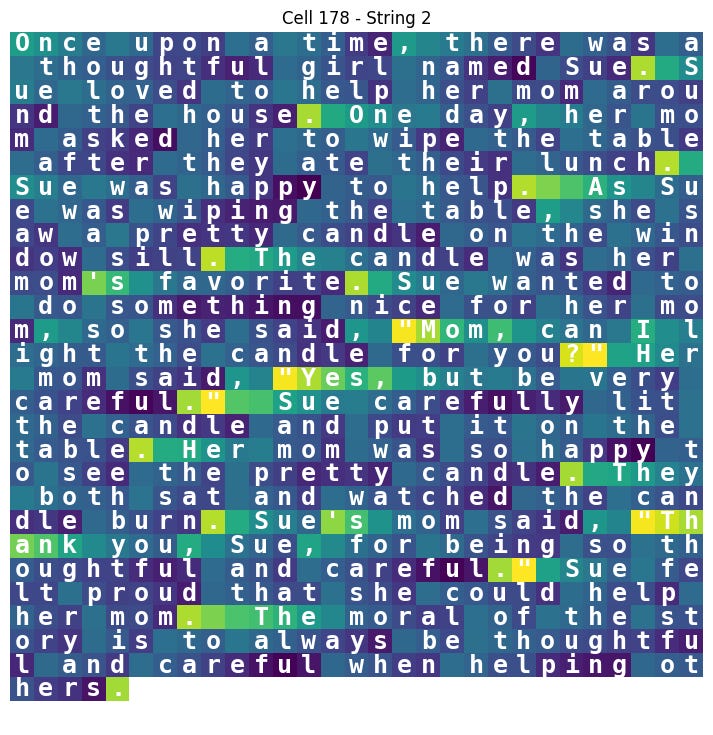

Here is an example heatmap and activation line plot from an example quoted string:

These plots suggest the cell is most excited for quotes, followed by punctuation, rather than being a state machine indicating inside quotes / outside quotes.

Nerfing Cell 178

Suppose we really don’t want quotes in our generated stories. For some reason, the stories with quotes keep the kid up at night, instead of putting them to sleep like a proper bedtime story should (probably due to the anticipation of the closing quote!).

Could we use our knowledge of cell 178 to prevent the model from generating stories with quotes? The tricky part is we don’t want to hurt model performance too bad (we can’t afford that!); we just don’t want quotes in the output. The problem is that cell 178 is influenced by and influences every other cell through the recurrent matrices in the gates and candidate cell state. Some of these cells I haven’t listed here (due to time and space constraints) seem “interested” in quotes suggesting that there is a quote circuit, a graph of cells that work together to deliver the overall quote capability. But perhaps we can get lucky by clipping the value of cell 178 just right so that quotes are not generated or generated less when we sample. If we clip the activation value so that it doesn’t exceed 0.8 (based on the max values above), then the cell should behave similar to the un-nerfed version for the majority of tokens except quotes. Hopefully this will limit the second-order effects on cells which depend on cell 178.

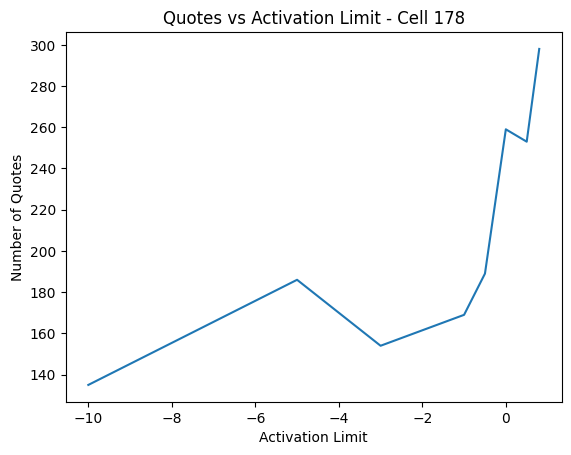

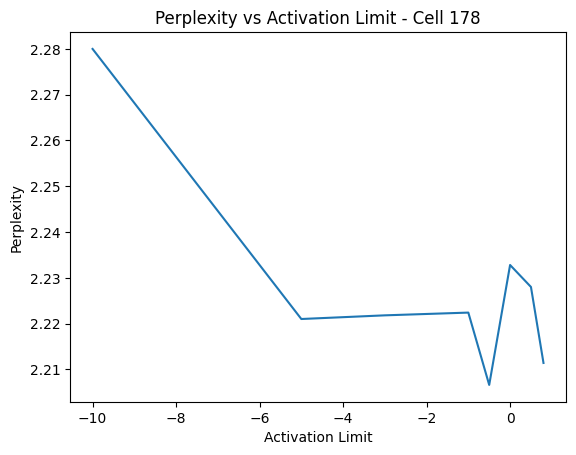

We can generate 100 stories without modifying cell 178 to get a baseline percentage of quotes, then generate new stories after clipping any value greater than 0.8 to 0.8. In each scenario we can measure the perplexity to see the total impact to performance and the total number of quotes in the string.

The baseline 100 stories without cell modifications gave a total of 363 quotes. The perplexity was 2.2271.

Clamping the activation of cell 178 to 0.8 resulted in 298 quotes, which is about an 18% reduction. The perplexity actually fell slightly to 2.2114. We can try to clamp with smaller values to see its affect on quote generation. Here are some plots for number of quotes generated and perplexity versus activation limit (0.8 is on the far right at 298):

It is interesting that we can limit the cell all the way to -5 before seeing hardly any change to perplexity. We do begin to start trading off less quotes for losses in perplexity after -5, but otherwise it seems we’ve definitely found at least one of the cells responsible for quote generation! To completely erase quotes would take more work tracking down the other cells that are working with cell 178.

Not bad for a quick peek under the hood of our LSTM. There are other things that would interesting that I didn’t cover, like tracking down the cells that influence cell 178 the most and vice versa. Also understanding what the most “exciting” input would be for a given cell. This is tricky since we are dealing with a sequence of inputs rather than just one. It would require carefully constructing a loss function to backpropagate into the input sequence, perhaps maximizing the autocorrelation (i.e. “trendiness”) of the cell activation curve in addition to the magnitude.